As of late December, 2019-nCoV emerged as the 3rd novel coronavirus in the past two decades, according to the New England Journal of Medicine. The CDC identifies it as the 7th known coronavirus, although there are likely more. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) of 2003 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) of 2012 imparted case fatality rates of 9.5% and 34.4% respectively. All three are zoonotic viruses, having animal reservoirs of disease. Elimination of outbreaks depends on ability to eradicate the virus from the human population and immediate animal reservoirs. SARS has been effectively contained, while MERS outbreaks from zoonotic spillover are still a threat. There is especially high risks for transmission of these diseases in health care settings. Nosocomial transmission, or hospital-acquired viruses, accounted for 58% of SARS and 70% OF MERS cases, where many immune compromised individuals are in close contact. These statistics will help guide epidemiologist and health professionals in how to best handle the current spread of 2019-nCoV.

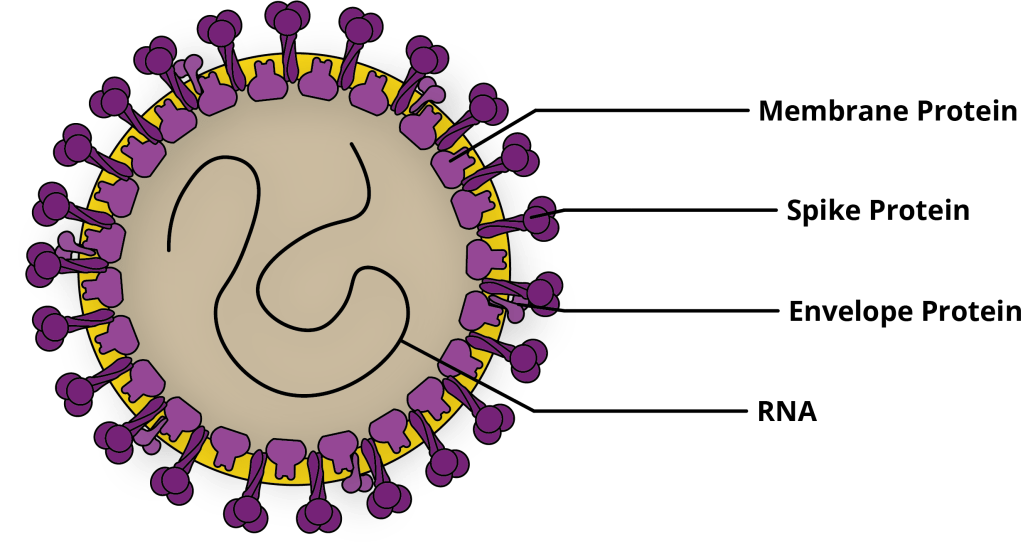

Shown above, viruses of the Coronaviridae family are named for their crown-like appearance. Protein spikes extend from these viruses’ envelopes in a uniform fashion, contributing to their specific actions in the respiratory tract. The genetic information contained inside the virus envelope is positive sense, non-segmented, single stranded RNA ranging from 26-32 kilobases (Kb) in size, which is large for an RNA virus. RNA viruses are much more susceptible to mutability because of the more frequent mistakes made by its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP) during genomic replication. Accumulation of mutations results in antigenic drift and contributes to virulence. With this ability to rapidly mutate, CoVs have found a variety of mammal hosts and increasing opportunity to infect human populations.

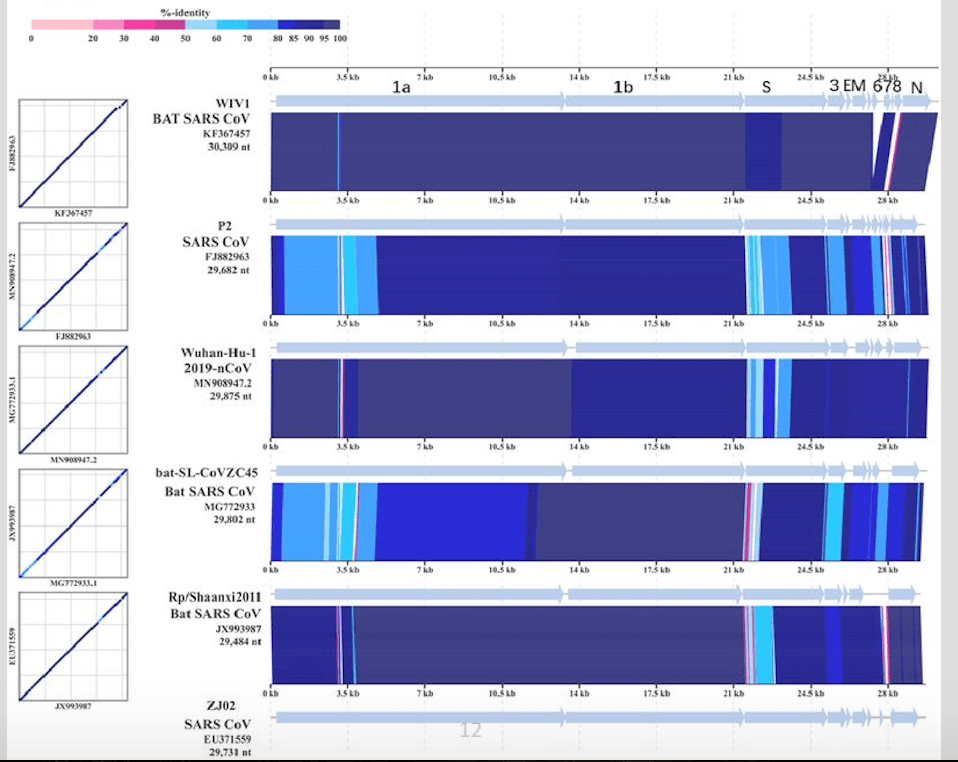

Phylogenetic analysis (left) of this novel coronavirus suggests it originated in bats, similar to the SARS coronavirus. However, the disease was pinpointed to stem from a seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, China when many workers and visitors of the location fell ill with fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Because bats are not sold here, the animal serving as the transmission vehicle has not yet been identified. Protein analyses were additionally carried out, specifically for the aforementioned spike (S) proteins which control the virus’s point of entry into host systems. This paper showed that the receptor binding domain of the 2019-nCoV S proteins had lower affinity for the expected angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor (ACE2) than the related SARS virus, which could confer reduced virulence. However, the recent spike in confirmed cases, indicating effective human-to-human transmission, leads these researchers to suggest that the novel virus may be actively evolving between human hosts or has a different receiving host protein. Constant monitoring and research is necessary to determine exactly how this new coronavirus is acting in the respiratory tract and how it can be prevented.

Questions left to answer:

- Are asymptomatic individuals able to infect others?

- How long is the virus’s incubation period?

- Can existing drugs compromise any of the virus’s polymerases or proteases, thus inhibiting infection severity?

- Which animal directly transmitted the virus, and how can this reservoir be contained?