The genes and environment of every person has created a unique ecosystem in which bacteria dwell and thrive. The microbiome, or the colonized microorganisms within and on the human body, has influenced every aspect of medical research in recent years as scientists are realizing the expansive roles bacteria play in metabolism and overall health. However, the differences in host microbial conditions are making it difficult to identify what a “healthy” microbiome consists of. One important aspect of the mutualistic relationships between humans and their microbiomes presents in the intestinal tract. Because so much research is conducted in the Western and developed worlds, there is a significant bias towards the health standards of particular nations. The conclusion being, a healthy microbiome in one context, could be completely useless in another.

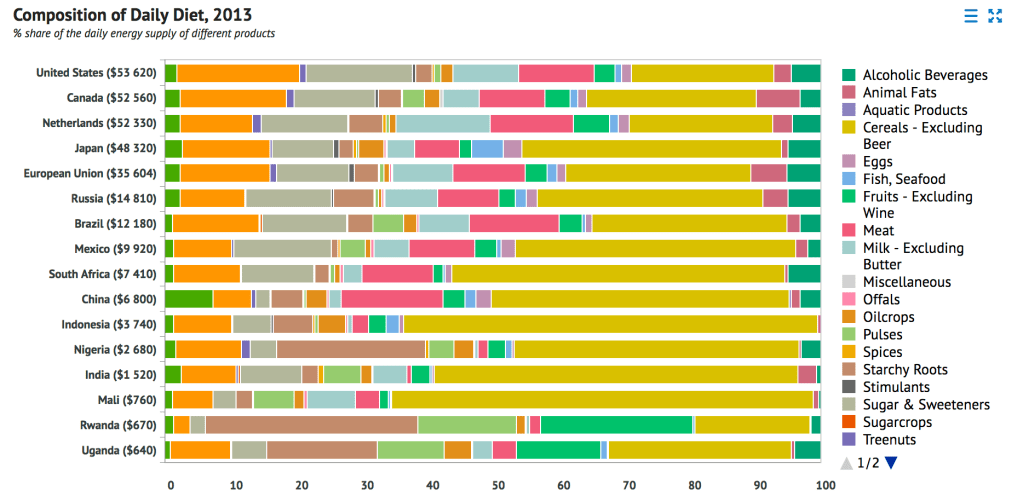

The figure above demonstrates the differences in diets across multiple nations. What a person eats affects what nutrients are being funneled to resident intestinal bacteria and therefore dictates which species thrive. Additionally, because the microbiome is passed in part via vertical transmission during birth, the lineages of bacterial colonization are somewhat consistent within families and general environmental conditions. With these observations, it can be concluded that healthy bacterial profiles will differ greatly between individuals. Because this variability has been passively identified, it begs the question: should people be taking action to actively manipulate their microbiome to better their health? To answer this question, however, researchers must determine the pro and con actions of typical resident microbiota.

Antibiotic overuse demonstrates a situation in which resident microbiota are actively altered, but with negative effects. Infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria results in almost 50,000 deaths a year in the U.S. alone. These drugs exert selective pressure for pathogens that are able to resist the antibiotic arsenal. Because antibiotics will inherently wipe out many bacteria in the body unintentionally, it also decreases the competition for colonization faced by pathogens. Normal flora can affect protect the body passively by way of increasing competition for resources, but also some species have a direct inhibitory effect via secretions. For example, Bacteriodes species can produce peptides inhibiting C. diff growth and colonization. Further exploration is necessary to determine the health benefits of normal flora, across different environments and cultures, in terms of normal metabolism and protective action. Advances in determining how to best nourish a healthy microbiome, tailored to individuals, could signify great progress in medical practice.