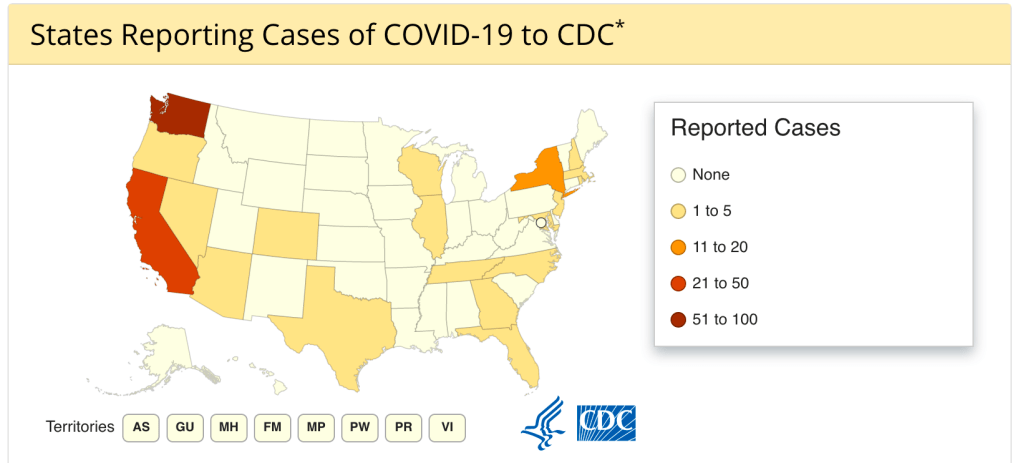

Past the stage of true containment, heath officials are urging people to become educated on how to reduce transmission of the COVID-19 virus rather than wait for a cure to emerge. In this age of transportation and technology, the spread of the 7th known coronavirus was inevitable. The number of reported cases in the U.S. likely underestimates the true extent of disease spread. A long and variable incubation period of 2-14 days increases the chances of unknowing hosts shedding disease in the community. As expected, the number of community acquired cases is beginning to outnumber travel-related cases in America. The consensus of medical professionals, and my microbiology professor alike is: wash your hands don’t touch your face (#WYHDTYF). Conveniently, this is the best method for reducing the spread of almost ALL infections!

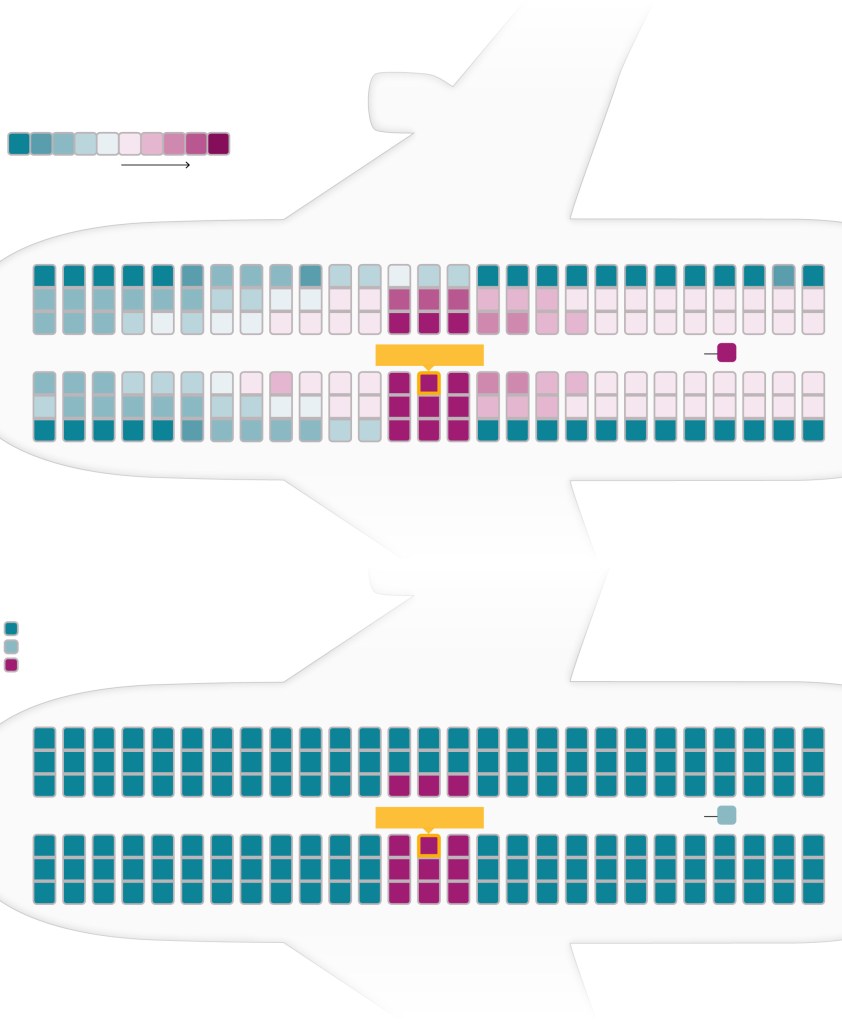

Most respiratory illnesses, and all other known coronavirus, spread by large droplet transmission. This means that respiratory secretions from infected individuals (which can include asymptomatic hosts) must enter through the eyes, nose, or mouth of another individual to infect them. These droplets usually fall within 6 feet of the secreting individual, and cover public surfaces. Suprisingly, this should hold true even on airplanes with constant air re-circulation. Large droplets are too heavy to be caught and will likely only endanger those closest individuals. Most viruses will only survive on fomites prior to drying. The specific lifetime of the COVID-19 particle is unknown, but expected to be between 3-12 hours. This transmission information reinforces that the best method of stopping the virus is for EVERYONE to control where their droplets fly (by covering your mouth with your elbow while coughing, for example), and for EVERYONE to wash their hands frequently with soap and water. One lucky thing about the coronavirus, is that its lipid envelope is easily destroyed by alcohol based hand sanitizers. This portable backup to handwashing has the potential to seriously reduce transmission of COVID-19.

This article, in a journal dedicated to intensive care research, outlines the lessons that we learned from the last two instances of novel coronavirus circulation (MERS and SARS). Although the diseases states differ, and human-to-human transmission seems to be more common with COVID-19, the impact on hospitals, healthcare workers, and the economy, are comparable. The author mentions availability of ICU beds, control of nosocomial transmission, and infection control goods supply, as issues that should be expected and planned for in the coming months. The need for a wealth of molecular and clinical research is also mentioned. Over Februrary 11-12, 2020 the research priorities were outlined in collaboration between the WHO and GLOPID-R, including a worlwide study that can independently analyze the effects of multiple interventions and their interactions.

It has been amazing to watch the massive influx of journal articles being published and reviewed in this time of crisis. For example, many labs are looking to identify a pre-exisiting drug or compound that may inhibit the receptor-binding-domain (RBD)-receptor interaction of the glycoprotein spike on this particular coronavirus. This study identified two chemotherapy drugs and food dye E155 as potent inhibitors of this site. Problems with widely declaring, as these researchers do, that these compounds may be used in medications to reduce disease severity include a lack of exploration of toxicity in the human body. What else might these compounds potently inhibit? Additionally, because glycoprotein spikes are what allow the virus to bind to target cells, this type of inhibition would like only be useful in early stages of incubation rather than in cases of severe disease. Despite these challenges, every scientific observation will be helpful in fully characterizing the virus we are battling.