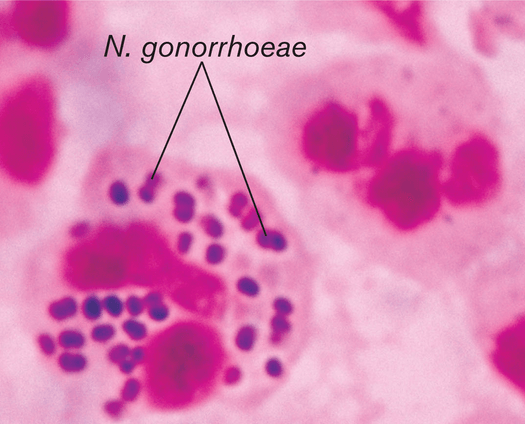

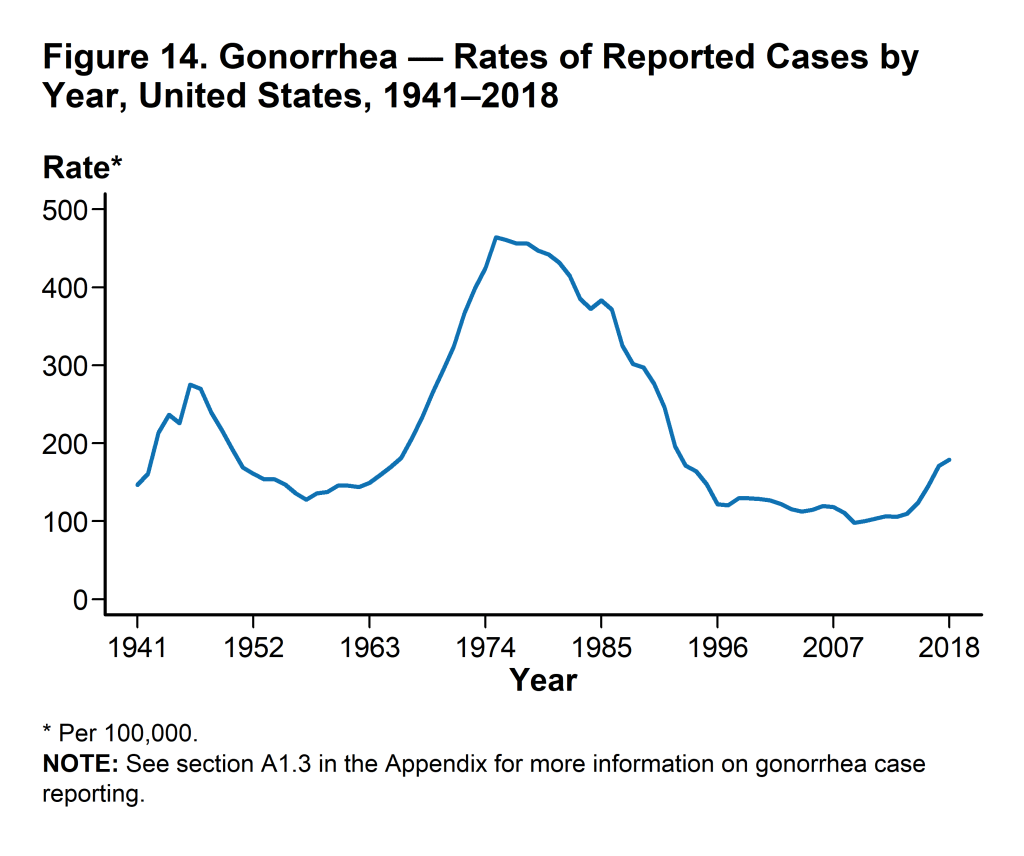

A 5% increase in gonorrhea was observed in the 2017-2018 calendar year, totaling 583,405 cases in the U.S. Notably, this number is an 82.6% increase from the historic low in 2009. This increase was accompanied by increases in all of the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia and syphilis. These changes are not due to chance. Taking a closer look at the epidemiology, treatment, and prevention of gonorrhea will reveal a major disruption in standards of care: antibiotic resistance. Gonorrhea is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram-negative fastidious diplococcus. It only resides in humans, making it a potential target for pathogen elimination. With pili, it is able to attach to non-ciliated columnar mucosal cells, which are present in the urethra, cervix, mouth, pharynx, rectum, and conjuctivia. They can live on the surface, or inside of host cells conferring protection from host defenses. Although infections are frequently asymptomatic, the inflammatory response induced by the bacterium can cause long-term damage in hosts including pelvic inflammatory disease in women, arthritis, and infertility in both sexes. Potential signs and symptoms differ between men and women, but include painful urination, urethral discharge, and abnormal vaginal discharge. The lack of noticeably severe symptoms contributes to widespread transmission and unreported infections.

Transmission occurs by vaginal, oral , or anal sex. Vertical transmission results in neonatal gonococcal conjunctivitis. Fluoroquinolones were the initial antibiotic of choice for treating this infection in recent years, until resistance spread most likely through horizontal gene transfer. Combination therapy of ceftriaxone (injected) and azithromycin is now recommended. Unfortunately, this dual-antimicrobial regimen is not predicted to be a long-term solution since susceptibility in isolates worldwide is already decreasing. The use of antimicrobials ironically induces the selective pressure that allows the most resistant strains to proliferate. The fact that many infections are asymptomatic means that patients could be given antibiotic treatment for other ailments that inadvertently make N. gonorrhoeae populations more resistant. These populations are then spread through condom-less sexual encounters. Additionally, there is no immunity conferred upon infection, meaning that one person can be infected multiple times. This expands the reservoir in which N. gonorrhoeae can develop and expand in capabilities.

A recent study explores the potential to curb the effects of antibiotic resistance in N. gonorrhoeae by preventing initial cases through vaccination. Renewed interest in a gonococcal vaccine was spurred by evidence that two meniningococcal vaccines may be partially protective against gonorrhea. The WHO is aiming to reduce gonorrhea incidence by 90% between 2018-2030. These researchers concluded that even in the worst-case scenario of untreatable infection (completely antimicrobial resistant) emerging, the goal is attainable if all men having sex with men (MSM) attending health clinics received a vaccine offering at least 52% protection for at least 6 years. In this study, MSM were used as the demographic after being identified as the group with the highest per-capita rate of infection in England. The main impact of this study is the assertion that even a mildly efficacious vaccine could dramatically reduce disease prevalence. This 2019 study dives further into an outer membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccine.