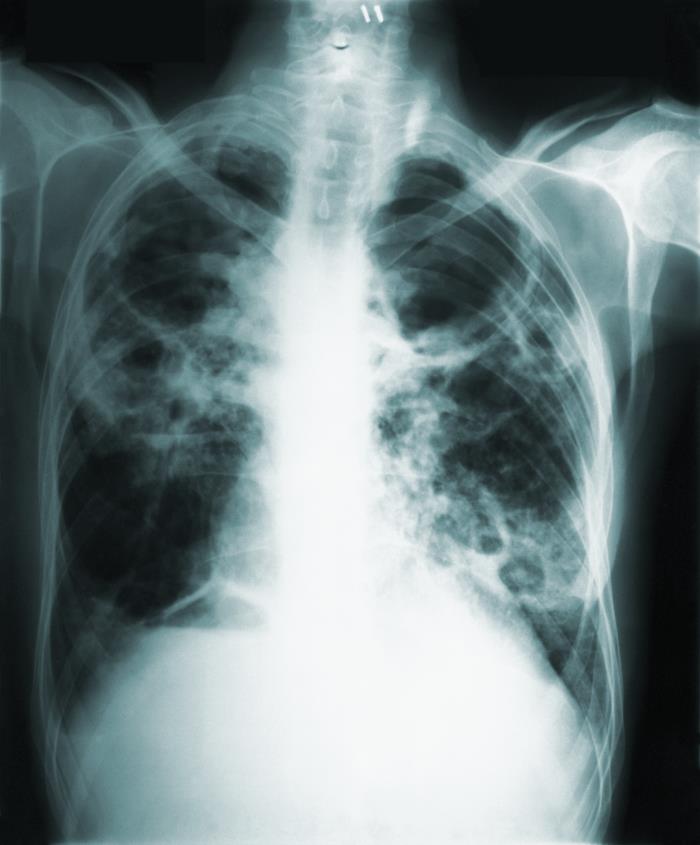

Tuberculosis, resulting from a Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in the lower respiratory tract, causes millions of deaths per year and poses a severe threat for immunocompromised individuals. It is the leading cause of death among people living with HIV, accounting for 32% of HIV deaths in 2018. Although long-term multi-drug treatment can usually eradicate the infection over the course of 6 months to 2 years depending on patient circumstances, the emergence of increasingly drug-resistant strains is impeding the current antibiotic cure. March 24th, in usual years, highlights endemic tuberculosis and the efforts being made to combat this deadly disease throughout the world. This year, the WHO emphasized the importance of maintaining access to TB treatment despite strained healthcare systems grappling with an influx of severe COVID-19 cases. Ironically, the symptoms of tuberculosis and severe COVID-19 may overlap: fever, persistent cough, and constant fatigue are common presentations resulting from an invasion of the lungs and an overworked host immune system. The global disruption unfortunately will only increase the number of individuals that miss diagnosis and treatment. This reality only reinforces the importance of following social distancing measures to slow the spread of COVID-19.

During a global pandemic, the efforts of hardworking research groups on the world’s usual plagues are often overlooked. However, sometimes desperate health officials attempt to extrapolate research from unrelated severe diseases as a beacon of hope for a chaotic public. Both scenarios are likely occurring for tuberculosis. Although research in many labs has been put on hold, a recent paper reveals the potential importance of inflammasome regulation in M. tuberculosis infected alveolar macrophages in disease clearance. The inflammasome response upregulates host inflammatory signaling, and the interruption of this signaling was found to affect the survival of M. tuberculosis. If drug resistance continues to counteract the effects of antimicrobials that target the bacterial DNA dependent RNA polymerase (like Rifampin) or formation of the mycobacterial cell wall (like Isonaizid), other methods of inhibiting disease are necessary to maintain effective treatment.

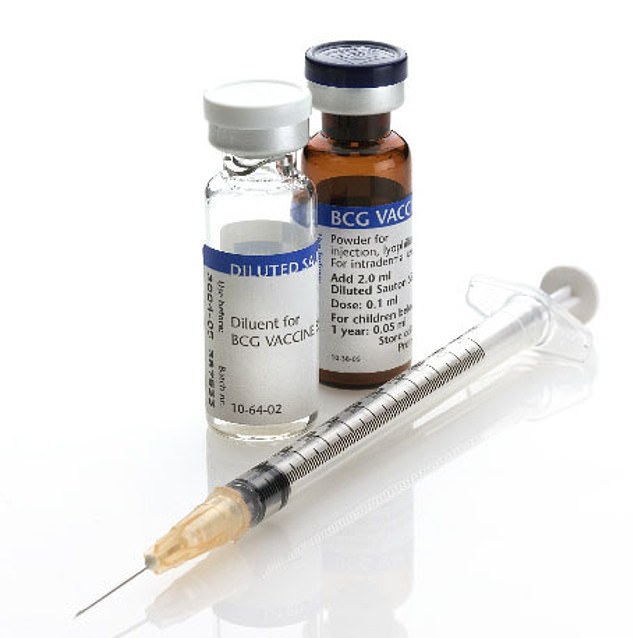

An example of redirecting focus from tuberculosis towards the COVID-19 crisis can be seen in many news headers over the past few days. For example, “Australian researchers trial TB vaccine to fight coronavirus.” Across the globe, years of research on other deadly diseases is being pushed into the light in hopes to cure COVID-19 rather than being perfected for its original purpose. At first glance, this headline is questionable. Besides the effect of the diseases in the lungs, the similarities between a tuberculosis and 2019-nCoV infection are few. It seems the only support given for running this large and expensive trial is a hope that it would boost “frontline,” or innate immunity against “germs.” Hmm. The vaccine being tested, BCG, is not administered in the United States because it is not very effective and interferes the the tuberculosis skin test. In this overview of the mechanism of the BCG vaccine in preventing TB, there is little evidence that there would be a strong response to a viral infection. However, Australian federal and state departments feel they have enough ground to run these trials after several studies indicated BCG vaccinated individuals may develop fewer viral respiratory tract infections than unvaccinated individuals. If the vaccine is found to confer protection against COVID-19, that would be a triumph. However, we should use these instances of overlapping research to also promote heightened awareness for other diseases and remind the public of the roles we should play every day of our lives to reduce transmission and increase treatment availability of all diseases.