Every few decades a major medical development revolutionizes standards of clinical care. Vaccines, antibiotics, rapid laboratory testing are just a few examples of advancements that quickly became essential aspects of the treatment and prevention of everyday diseases. Personalized medicine, capitalizing on unique genetic signatures and self immune cells, has been taunted as the next revolutionizing aspect of medicine. While vaccines and antibiotics form a catch-all net that protects a majority of the public equally, personalized medicine in the form of gene and t-cell therapy proposes treatments that have the potential to target cancer, HIV, HPV, and many other serious infections that often leave individuals at a serious disadvantage to current protective measures of healthcare. You may have noticed, but the revolution of personalized medicine has yet to materialize. This post explores the current state of research specifically in chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and its potential to treat HIV, based on reported successes in hematological malignancies including pediatric leukemia. The semblance between these conditions, in terms of circulating non-stationary leukocyte infection, gives hope that appropriate T-cell drug targets could be developed to clear latent HIV infiltration.

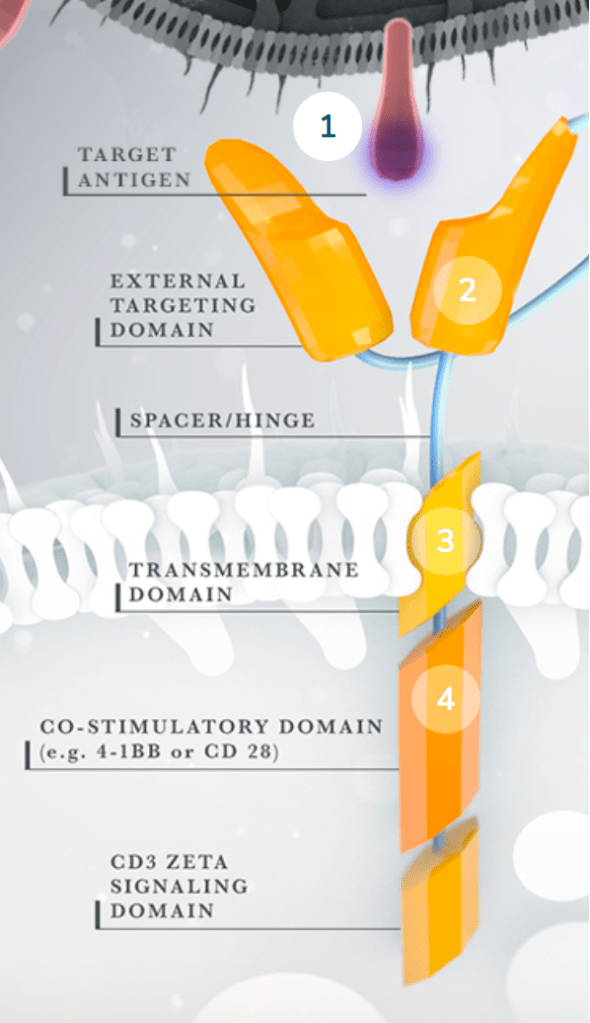

The cost of one round of CAR T-cell treatment in the United States is between $373,000 and $500,000. In theory, only one treatment is necessary. However, this cost, if (somehow) it doesn’t already sound unimaginable, fails to include hospital fees and potential treatment of side effects which can easily drive the price tag towards one million dollars ($1,000,000). The following description of CAR T-cell treatment may elucidate a small (small) portion of the aforementioned cost, as complicated, precise, and personalized science is involved. The therapeutic plan involves isolating T-cells from the patients blood, engineering them to specifically target the malignancy/infection, and re-infusing an appropriate dose. The usual adaptive immune response requires dendritic cells, or other antigen presenting cells (APCs), to present processed pathogenic antigens to a reservoir of T cells with unique antigen receptor domains. In theory, there should be enough natural variation in a person’s T cell reservoir to recognize a sufficient variety (25 million- 1 billion) of pathogens and carry out an effective immune response. The advantage of creating CAR T cells includes the potential for a more rapid and specific response. Instead of waiting for dendritic cells to activate 10 out of 1 billion T cells, that will then proliferate in attempt to find that specific antigen and begin killing the infected cell, these artificial fighters bypass APCs and can immediately begin firing away at infected cells.

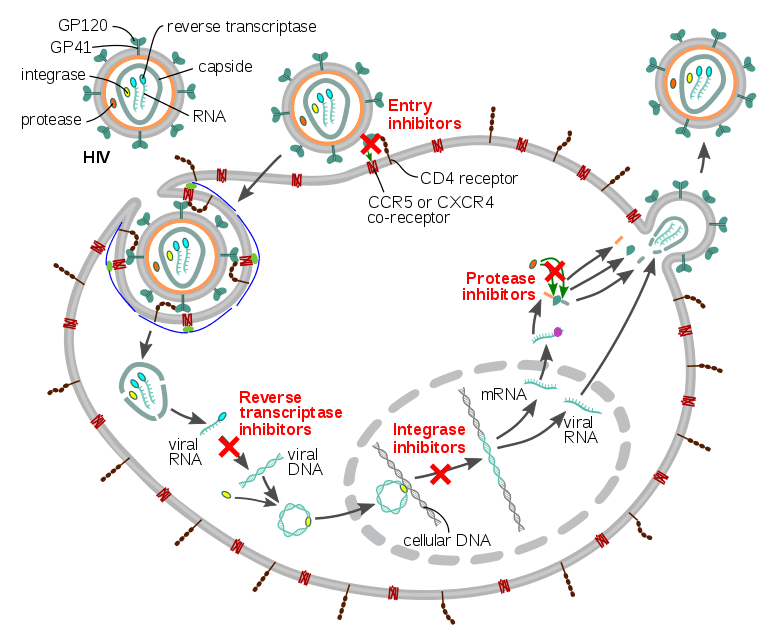

HIV infects helper T cells. These T cells, whose function is to rid the body of pathogens and abnormalities, are impaired against HIV. By hijacking the host’s protective immune system, the HIV virus inhibits its own destruction. An outside source of fighters is necessary to combat the infection. CAR T cell therapy provides a potential solution because the engineered T cells could recognize specific HIV antigens, such as the glycoprotein spike on its viral envelope, and express epitopes that confer resistance to HIV infection themselves. While current antivirals rely on actively replicating and infiltrating virus, CAR T cells have the potential to attack latent HIV reservoirs in patients leading to possible disease clearence. Although this pursuit should continue in rigor, potential side effects should be equally explored. Severe cytokine release syndrome (sCRS) is possible, inducing a systemic inflammatory response that threatens every major organ in the body. Neurological toxicity is linked in this progression with building cytokine levels and CAR T cells that could cross the blood-brain barrier. Ambitious treatments serve higher risk, but the worldwide battle against HIV is not over.