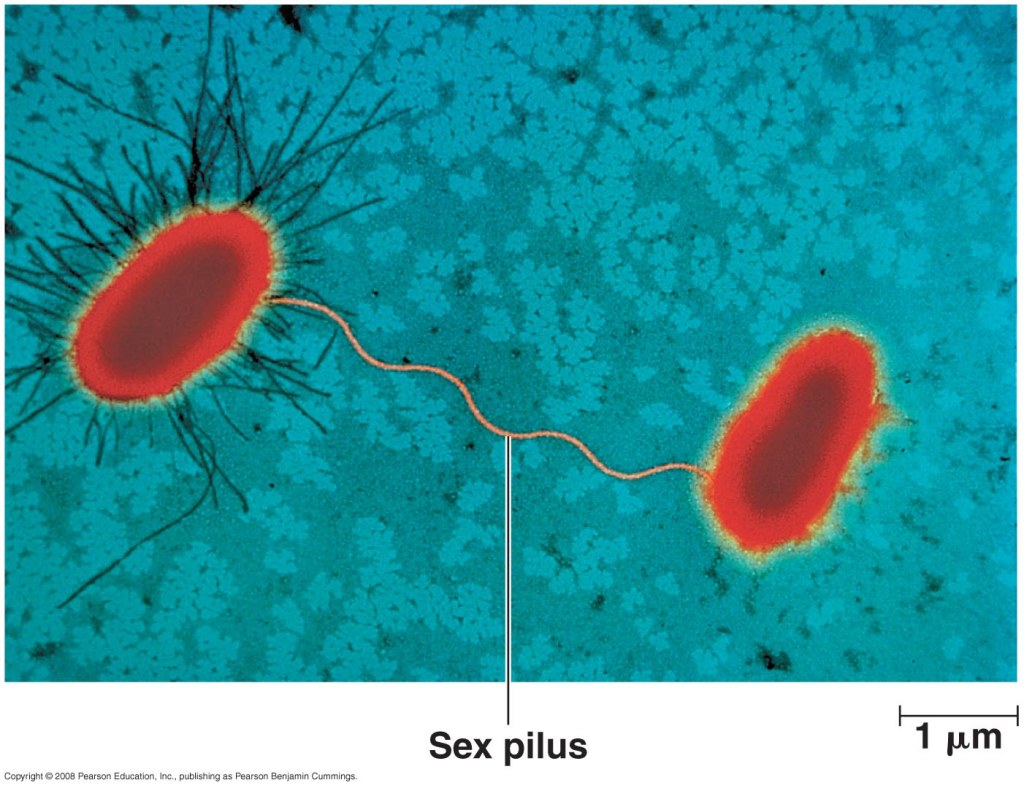

Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928. However, the purification and production process was not dependable until the early 1940s when scientists Howard Florey and Ernst Chain built on Fleming’s original findings. In 1942, the first American patient was treated with the antimicrobial drug. Penicillin inhibits cell wall synthesis in certain bacterial species, resulting in cell death. Since then, multiple targets for antimicrobial action have been identified including inhibition of protein synthesis, nucleic acid synthesis, and metabolic pathways. Researchers then and now have sought to synthesize new chemical structures to treat bacterial infections via the aforementioned targets. It is almost incomprehensible that less than 80 years ago, antibiotics were unknown in everyday healthcare. Even more notable, is rate at which antibiotics are becoming insufficient in treating common bacterial infections. In addition to random mutation, several mechanisms developed to transfer novel genetic info to bacteria within and between species. Because bacteria multiply exponentially with quick turnover, genetic acquisitions that confer resistance can build rapidly in a population.

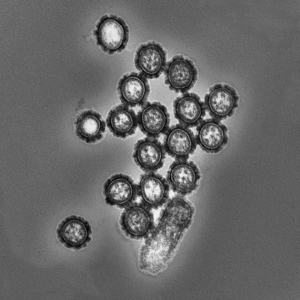

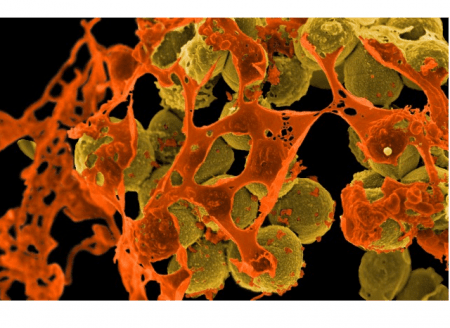

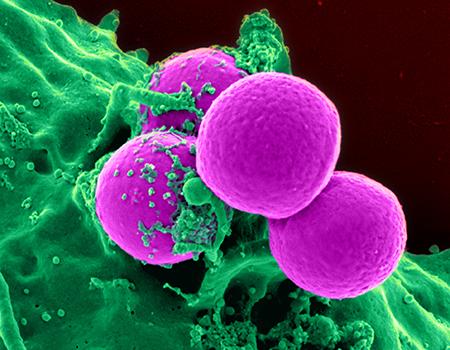

A case study following the development of antibiotic resistance in strains of Staphylococcus aureus reveals the fight of bacteria against our “miracle drugs.” S. aureus is a gram positive coccus, appearing in grape like clusters under a microscope. Although many people are normal carriers of this bacteria, it poses a serious threat to immunocompromised patients and is the leading cause of healthcare-acquired infections. This study outlines the frequently changing antibiotic resistance profile of S. aureus and some surveillance methods in place. The very first test of penicillin was given to a 43-year-old English policeman with a life-threatening S. aureus infection from rose thorn scratch near his mouth. After the injection, he made a remarkable recovery over a few days. When the small supply ran dry, his infection unfortunately returned in full form. However, 95.2% of the S. aureus recovered from HIV patients in the linked study was highly penicillin resistant, 84.6% were cephalexin resistant, and in the year 2017, 86% were methicillin resistant (compared to 51.8% in 2012). In today’s times, the policeman would not exhibit any recovery after an injection of penicillin. From year 0 to year 78, the bacteria have acquired an unimaginable number of genetic changes conferring protection, and serving as an amazing example of evolution in action. Methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) currently is most threatening in healthcare settings.

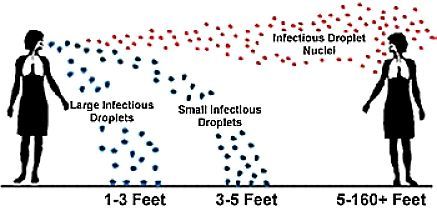

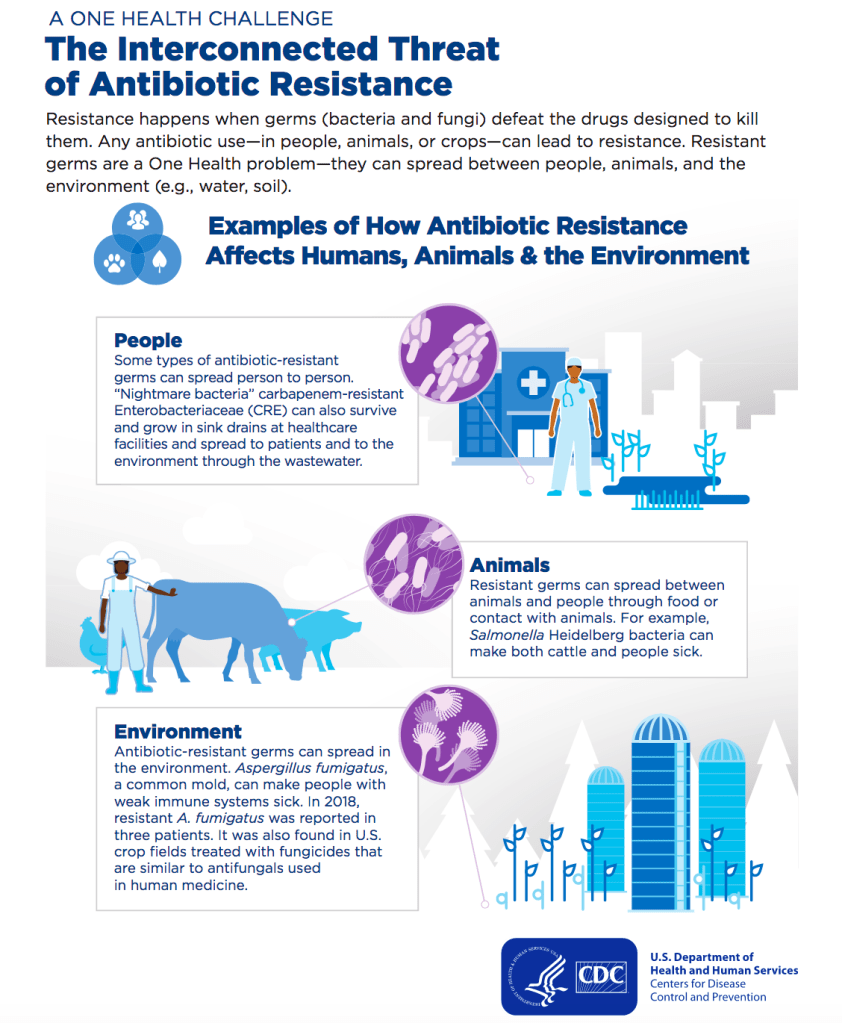

The misuse of antibiotics, in humans and animals, dramatically increases the rate at which bacterial populations demonstrate new forms of resistance. When a group of bacteria is exposed to an inhibiting or bactericidal substance, selective pressure is exerted against susceptible strains. The few resistant individuals will then clonally expand, rendering a subsequent round of the antibiotic useless. On a large scale, when antibiotics are used unnecessarily, this selective pressure persists, constantly singly out the most fit bacteria to drive future populations. The WHO expresses the urgency with which antimicrobial needs to be addressed. The CDC also outlines actions that people can take in their everyday lives to reduce the speed at which antimicrobial resistance is developing. Antibiotics are crucial to continuing current health standards and protect a huge community of susceptible individuals from life-threatening infections. 78 years of antibiotics is not a lot. Global action is necessary to ensure the continued effectiveness of the world’s miracle drugs.